The History of Emoji: Japan Gave the World a New Language

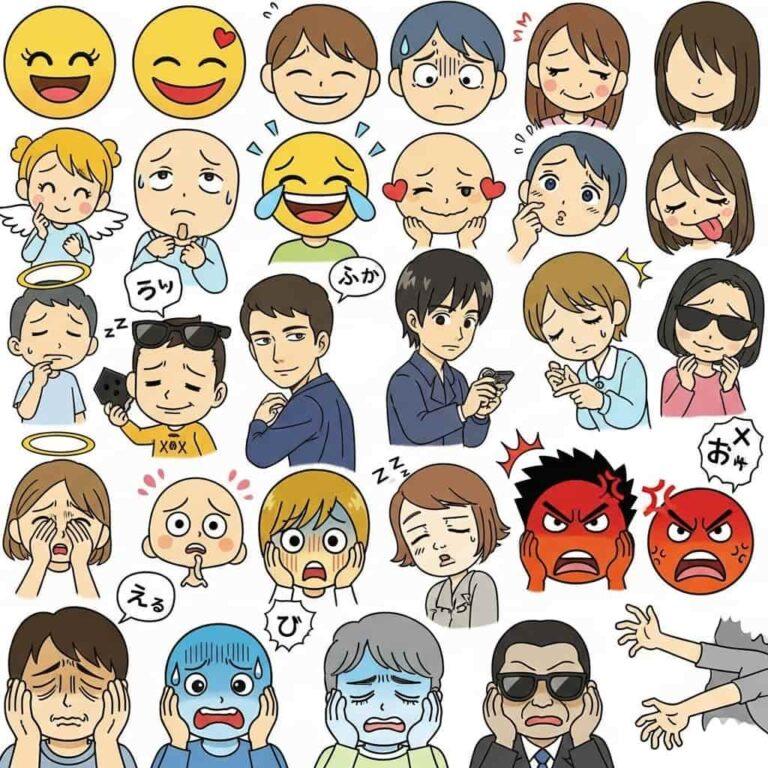

Emoji, derived from the Japanese words 絵 (e: picture) and 文字 (moji: character), are pictographic symbols used to convey emotions, actions, and ideas in digital communication. Their origins lie in Japan’s high-context culture, as a way to bring back non-verbal cues lost in text. Prior to Emoji Japan had Kaomoji, meaning face characters, such as (^_^) for happiness or (T_T) for sadness, created from ASCII characters. These Kaomoji developed along with Japan’s mobile phone culture in the 1990s through pagers and SMS. This set the stage for Shigetaka Kurita’s 1999 creation of the first modern emoji set for NTT Docomo, to eventually Unicode Consortium in 2010, transforming digital communication worldwide.

Table of Contents

Japanese High Context Culture created the right Environment for Emoji3

Japanese culture relies heavily on high-context communication. People often avoid direct expressions and speak euphemistically, always considering the feelings and status of others. The speaker adjusts word choice and expression depending on the situation and relationship between the people involved.

The Japanese language encodes levels of politeness directly into its grammar. Speakers modify verbs based on the relative status between the speaker, the listener, and the person being discussed. In this kind of communication style, people rarely express emotions or intentions explicitly. Emoji and emoticons naturally evolved as tools to fill in these gaps.

Emoji help clarify emotion and intent in situations where written language alone might seem vague or impersonal. People use them to avoid misunderstandings, soften messages, or express feelings without being too direct. Each emoji acts as a small tool for expressing tone, helping users fine-tune the subtle meanings that plain text often loses.

Japanese culture places great value on reading between the lines, or as they say in Japan, 空気を読む (kuuki o yomu), which means reading the air. Without shared physical presence or facial expressions, people lose much of that unspoken context. Emoji restore some of those missing non-verbal cues, allowing conversations to feel more fluid and natural—even in digital spaces.

Digitalization of Japanese writing and Handheld devices in Japan

Japanese Mobile Phone Culture

Emoji did not emerge from Japan by accident. They developed as a direct result of Japan’s unique mobile culture. Japanese phones sparked the emoji revolution long before the iPhone changed the global landscape. Apple may have gone global, but Japan led first.

Japan’s pioneering mobile phone culture—called 携帯文化 (keitai bunka), or mobile phone culture—created the ideal environment for emoji to grow. Before smartphones, Japanese users already had advanced phone features. These included cameras, mobile internet, and customizable messaging.

Even before cell phones, pagers—called ポケベル (pokéberu), or pocket bell—let users send short numeric and symbol-based messages. For example, users sent a musical note to express emotion. This started the trend of symbolic emotional expression in messages.

Once short mail (SMS) became popular, character limits forced users to find new ways to express themselves. As a solution, users began creating 顔文字 (kaomoji), or face characters. These used symbols to create emotional expressions.

Instead of 😊, they typed 🙂 — or more creatively, (^^), (T_T), or (¬¬). These felt richer and more flexible.

Kaomoji relied on ASCII characters but offered much more range than Western-style emoticons, which often stayed tilted and limited. As texting grew, so did the emotional need for subtler, visual ways to communicate beyond written text.

Japan’s mobile culture drove the evolution from kaomoji to emoji. It didn’t just enable emoji—it demanded them.

Kaomoji in written expression in Japan

Before emoji, people used emoticons—typographic faces like 🙂 or :-(—in online chats during the 1980s and 1990s. Scott Fahlman proposed the first smiley using ASCII characters in the early 1980s to express emotion in plain text. Unicode later added the smiley to its Miscellaneous Symbols block in 1993, formalizing it in digital communication.

Meanwhile, Japan developed a parallel system that remains more expressive and visually complex than early Western emoticons.

This brings us to 顔文字 (kaomoji), or face characters, which evolved alongside emoji but deserve separate attention. Although I’ll keep it brief here, kaomoji shaped emoji’s earliest visual language, especially in Japan’s first emoji sets.

The first known kaomoji appeared in 1986, when わくねこ (Wakuneco), aka Yasushi Wakabayashi, posted it on ASCII NET.

He created the now-classic (^_^), which became the base template for countless expressions.

Kaomoji focus on the eyes, over the mouth, using forms like (°_°), (T_T), and (^o^) to show nuanced feelings. This reflects the Japanese cultural value placed on reading emotion through the eyes rather than the mouth. Sometimes only the eyes are used like, ^^ .

But, the mouth is still an important part of most the Kaomoji.

Unlike Western emoticons, kaomoji face forward and require no head-tilting, aligning with Japanese design and manga aesthetics. Frankly, I never understood why American emoticons didn’t evolve the same way—Japan’s approach simply feels more expressive.

Even today, people still use kaomoji actively, not just nostalgically. They offer expressive depth far beyond standard emoji.Kaomoji go beyond facial emotions.

Kaomoji gained popularity in the 1990s through pagers (ポケベル pokéberu), SMS, and early email on Japanese mobile phones. Grassroots online communities like 2ちゃんねる (ni-channel) spread kaomoji through message boards and BBS forums. By the 2000s, people compiled massive lists in 顔文字辞典 (kaomoji jiten), or kaomoji dictionaries, pre-installed on phones.

Many users still prefer kaomoji because they feel more versatile, personal, and rich in meaning than emoji alone.So although emoji went global, kaomoji grew independently from Japan’s digital culture and still carry a strong voice.

The History of Emoji: Exploring the Art of Kaomoji

Emoji have become a universal language in digital communication, but their roots trace back to creative text-based expressions, particularly in Japan with kaomoji. Unlike modern emoji, which are standardized pictographs, kaomoji are intricate faces and symbols crafted using ASCII characters, punctuation, and sometimes Japanese characters. Emerging in the 1980s on Japanese online forums, kaomoji allowed users to convey emotions and actions in a purely text-based environment, long before graphical emoji were introduced by Shigetaka Kurita in 1999. The term “kaomoji” comes from the Japanese words kao (face) and moji (character), reflecting their purpose: to create expressive “faces” with keyboard characters. Kaomoji are celebrated for their creativity and versatility, capturing a wide range of emotions, actions, and cultural nuances. Below, we explore various kaomoji categories and their meanings, showcasing their charm and expressiveness.

Laughter

Kaomoji in this category express joy, amusement, or laughter, often with playful and exaggerated features:

- ^ ^: A simple, cheerful smile, emphasizing squinted eyes to show happiness.

- ^^: Similar to ^ ^, but using full-width characters for a bolder look.

- (^^): A classic happy face, with parentheses framing the joyful eyes.

- ^o^: Adds a small mouth, suggesting a gleeful or excited chuckle.

- ^_^: A balanced, friendly smile, widely used for general happiness.

- ( ̄▽ ̄): A mischievous grin, with a wide, toothy smile indicating playful laughter.

- )^o^(: A dynamic, energetic expression, as if the face is bouncing with joy.

Cuteness

These kaomoji aim to evoke cuteness, often with soft or shy expressions:

- (≧ω≦): A blushing, excited face with big eyes, radiating adorable enthusiasm.

- (๑˃̵ᴗ˂̵): A delicate, endearing expression with a small blush, perfect for kawaii vibes.

- (๑╹ω╹๑ ): A gentle, wide-eyed look, emphasizing innocence and charm.

Greetings

Kaomoji for greetings often mimic physical gestures like bowing or waving:

- (__): A simple bow, showing respect or a polite greeting.

- (^^)/: A cheerful wave, as if raising a hand to say hello.

- <(_ _)>: A deeper bow, conveying gratitude or apology.

- m(_ _)m: A formal bow with hands on the ground, often used to say thank you or sorry.

Shy/Embarrassed

These kaomoji capture shy or flustered moments:

- ( ´艸`): A giggling, blushing face, hiding shy excitement.

- (/ω\): A bashful expression, as if covering the face in embarrassment.

Creepy/Gross

For creepy or unsettling vibes, these kaomoji are deliberately eerie:

- (๏д๏): Wide, shocked eyes with a distressed mouth, suggesting something disturbing.

- (꒪ཀ꒪): A grimacing face, evoking discomfort or disgust.

Love

Romantic or affectionate kaomoji, often featuring hearts:

- (´ε` )♥: A kissing face with a heart, expressing sweet affection.

- (♥ω♥*): A dreamy, love-struck expression with sparkling eyes and hearts.

Movement

These kaomoji suggest action or motion:

- ε=┏(·ω·)┛: A running figure, with arms and legs in motion, conveying energy or escape.

Panic/Nervousness

For moments of anxiety or urgency:

- (^^;: A nervous smile with a sweat drop, indicating mild unease.

- (´Д`): A stressed-out face, wide-eyed and panicking.

- (;´∀`): A forced smile with sweat, showing awkward nervousness.

Disappointed/Sad

These express subtle sadness or letdown:

- ( .. ): A minimalist, droopy-eyed face, quietly disappointed.

- ( ´△`): A more pronounced sad expression, with a trembling mouth.

Sleepy

For tiredness or sleepiness:

- (-_-) zzz: A sleeping face with “zzz” to mimic snoring.

- ( ˘ω˘ )スヤァ…: A dozing face with a soft sleeping sound.

- (@ ̄ρ ̄@): A relaxed, drooling sleep expression.

Sad

Heartfelt sadness or distress:

- (><): A crying face with clenched eyes, showing deep sorrow.

- (_): Wide, teary eyes, overwhelmed with sadness.

- ( ´△`): A trembling, melancholic expression, also seen in disappointment.

Anger

For frustration or rage:

- (;`O´)o: A shouting, angry face with clenched fists.

- ( *`ω´): A pouting, irritated expression with puffed cheeks.

- ( ̄^ ̄): A stern, glaring face, radiating defiance.

Surprise

Capturing shock or amazement:

- (·◇·): Wide, round eyes with a small mouth, showing astonishment.

Kaomoji remain a beloved part of digital culture, offering a playful and artistic way to express emotions. Their evolution into modern emoji highlights their influence, yet their text-based charm continues to thrive in online communities, especially in Japan.

The Emoji Genesis

The first Emoji and digital pictograms

We could trace symbolic computing characters back to the 1970s when Zapf Dingbats introduced the first non-alphabetic symbols.

These symbols still influence emoji today, and many remain part of modern Unicode character sets. However, let’s focus on the mobile culture that emerged in Japan, which shaped emoji more directly and visibly.

In the late 1980s and early 1990s, people used PDAs and ポケベル (pokéberu), or pagers, before phones evolved.In 1988, Sharp released the PA-8500, a PDA featuring over 100 pictograms like smiley faces and crabs.

These pictograms marked one of the first emoji-like sets embedded into consumer tech for daily communication.Two years later, NEC launched the PI-ET1 PDA, which included more symbolic characters and even a customizable face editor.

This device allowed users to edit faces, showing early interest in emotional expression within text.Despite these innovations, neither Sharp’s nor NEC’s pictograms gained widespread adoption or industry standardization.

These experiments remained isolated and proprietary, yet they laid the groundwork for what emoji would later become.

Docomo and Shigetaka Kurita

The modern emoji era began with NTT Docomo, a major Japanese mobile carrier that shaped early mobile culture. In 1995, NTT Docomo added a heart symbol to its ポケベル (pokéberu), or Pocket Bell pagers, used by teenagers.

This symbol let users express affection quickly and nonverbally, which made messaging more emotional and engaging. Teenagers loved the heart icon, and their enthusiastic use revealed a strong demand for visual expression in short messages.

In 1999, Shigetaka Kurita, a 25-year-old interface designer at Docomo, created the first complete emoji set. He designed 176 emoji for the i-mode mobile internet platform, which Docomo launched in February of that year.Each pictogram measured 12×12 pixels and conveyed meaning compactly within i-mode’s 250-character text limit.

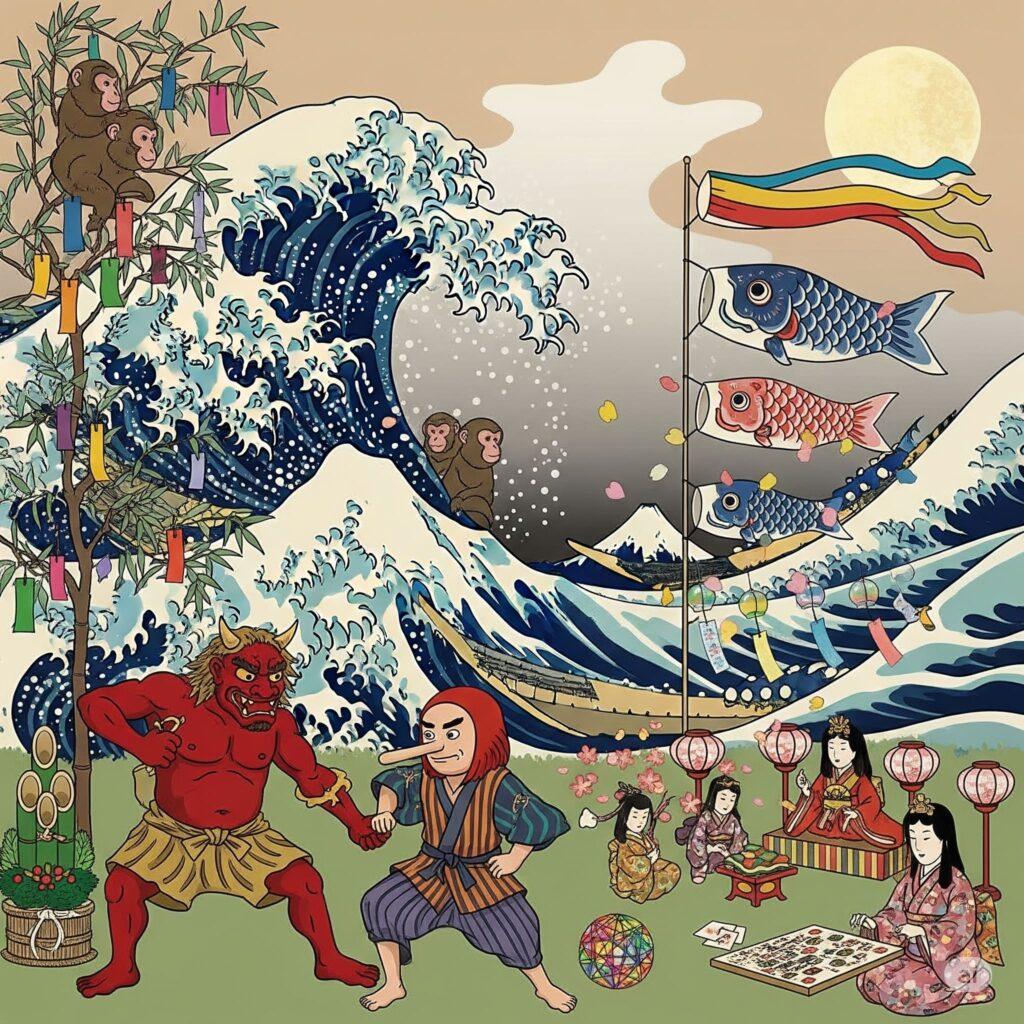

Kurita wanted emoji to function practically, helping users navigate weather, events, and communication with visual clarity. To build this visual system, Kurita drew inspiration from several Japanese sources and visual traditions.

First, he looked to 漫画 (manga), or Japanese comics, especially 漫符 (manpu), symbolic marks that show emotion like sweat 💦. Next, he incorporated weather pictograms, such as ☀️ for sun and ☁️ for clouds, as clear and familiar signs. Then, he borrowed from 漢字 (kanji), or Chinese characters, and Japanese road signs, known for visual clarity. Finally, he rooted the emoji in local culture, including symbols like ♨️ for hot springs, 🍙 for rice balls, and zodiac signs.

This grounding in Japanese daily life made emoji feel familiar, intuitive, and deeply local despite their digital form. Kurita’s emoji avoided human faces, instead emphasizing function, clarity, and variety, such as tech symbols and traffic icons.

Unlike earlier pictograms, he used color and embedded the set into the Shift JIS character encoding system. This approach allowed emoji to transmit as normal text, rather than as separate image files.

These emoji didn’t just stay local—they marked the start of a visual language that would spread worldwide.

SoftBank and the Poop Emoji

NTT Docomo popularized emoji, but they didn’t launch the first set. Another company beat them to it. In 1997, SoftBank’s J-Phone SkyWalker DP-211SW included 90 monochrome emoji, two years before i-mode’s debut.

This early set featured emoji for numbers, sports, time, moon phases, and daily life. Even though J-Phone’s pager sold poorly, its emoji set influenced future visual designs across platforms.

One icon from this set stood out: the 💩 Pile of Poo emoji.

うんこ - Several Types of Poop in Japanese It is no secret that the popularity of poop has taken off in the last couple years. Partially it m...Japanese Universe

In Japan, people call poop うんち (unchi), meaning poop or stool, and treat it as funny and harmless. They consider it 可愛い (kawaii), which means cute, instead of gross or offensive.

This cultural framing gave the 💩 emoji wide acceptance, not just in Japan, but globally. Designers shaped it like a swirl of soft-serve chocolate ice cream, making it look absurd but harmless.

That image connects to manga culture, where poop often appears as a joke or gag. You’ll often see うんち (unchi) used in manga aimed at children to evoke laughs and silliness.

SoftBank didn’t invent this poop shape, but they introduced it to the digital world. Digitizing it, they bridged manga humor with mobile culture, making 💩 an internet icon.

The poop emoji flushed into global use, landing next to heart emojis in messages everywhere.

Globalization of Emoji

Mojibake

In the late 90s and early 2000s, Japanese mobile carriers created separate, proprietary emoji systems without interoperability. Each carrier locked emoji into its own network, so people couldn’t send or receive them properly across platforms.

This incompatibility led to frequent garbled text, known in Japanese as 文字化け (mojibake), which means text scrambling. Mojibake occurred when systems misread character encoding, displaying random symbols instead of Japanese text.

People encountered mojibake frequently in email, websites, and file names, especially in Japanese-language environments. Developers hadn’t yet unified encoding standards, so many browsers and devices struggled with non-Western characters.

Japanese users turned to workaround tools, including apps and websites that could fix mojibake by converting encoding. Many people also tried to right-click and change character encoding manually, though this often failed to fix the issue.

Although modern systems rarely display mojibake, older users still remember how common and frustrating it used to be. By 2005, Japanese carriers began coordinating their emoji systems to allow limited cross-platform communication.

However, true emoji standardization took years and required global coordination far beyond Japan’s domestic carriers. Only after the Unicode Consortium adopted emoji in 2010 did seamless, international emoji communication become possible.

Unicode Consortium and Globalization of Emoji

The global adoption of emoji required standardization. This step ensured compatibility across platforms. Eventually, it mostly eliminated mojibake (もじばけ, mojibake), meaning character corruption.

The Unicode Consortium led this effort. Founded in 1991, this nonprofit maintains universal text encoding standards. Major tech companies like Apple, Google, Microsoft, and Adobe joined as members. Individual contributors and government representatives also participated.

Between 2008 and 2009, Google and au by KDDI pushed for emoji inclusion. They petitioned the Unicode Consortium, seeing emoji as a global communication tool. Separately, two Apple engineers, Yasuo Kida and Peter Edberg, submitted a detailed proposal in 2009. Their plan expanded Shigetaka Kurita’s original set to 625 emoji.

In 2010, Unicode version 6.0 officially added 625 emoji. These were encoded in the Supplementary Multilingual Plane (SMP). Now, emoji could coexist with other scripts. Standardized encoding ensured consistent display across devices. However, visual designs still varied by platform. For example, Apple’s hamburger emoji arranged toppings differently than Microsoft’s.

Apple and SoftBank’s Role

Global emoji adoption required standardization. Tech companies needed consistent displays across platforms. This effort eventually eliminated mojibake (もじばけ, mojibake), meaning garbled text.

The Unicode Consortium led the process. Founded in 1991, the nonprofit maintains universal text standards. Major members include Apple, Google, Microsoft, and Adobe. Governments and individual experts also contribute.

Google and au by KDDI proposed emoji in 2008–2009. They urged the Unicode Consortium to adopt emoji as a global tool. Meanwhile, Apple engineers Yasuo Kida and Peter Edberg submitted a 2009 proposal. It expanded Shigetaka Kurita’s original set to 625 emoji.

Unicode 6.0 added emoji in 2010. The update placed 625 emoji in the Supplementary Multilingual Plane (SMP). Now, emoji worked alongside other scripts. Standard encoding prevented display errors. However, designs still varied—like Apple and Microsoft’s different hamburger emoji.

After Unicode, Globalization of Emoji

Emoji submission to Unicode starts with passionate individuals or organizations. They propose new designs via the official Unicode Emoji Proposals page (https://unicode.org/emoji/proposals.html). Next, they submit detailed documents outlining the emoji’s purpose and cultural significance. The review process engages the Unicode Technical Committee actively. They evaluate each proposal for clarity and global relevance. Then, they discuss feedback to refine or approve the design. Cultural representation matters greatly in this process.

The emoji submission form asks for descriptions of multiple meanings, use in sequences, whether the submission is representing something new, and distinctiveness. The emoji should be recognizable and visually iconic, representing a class of entities rather than a specific instance.

Approval occurs after rigorous voting by committee members. They finalize designs for the next Unicode update. Subsequently, tech giants like Apple and Google implement these emoji worldwide. Community input shapes the outcome too. Fans share ideas on platforms like X, influencing future submissions. Finally, approved emoji enrich digital communication globally each year.

So, not Emoji are global and people all over the world use them. Different cultures may use one Emoji one way that another one would not. Now that Emoji are global there is more of a push to have it be more representative of a global society. This means having representative Emoji of different groups, and having neutral Emoji that people can use cross-culturally. However, the Japanese roots are still there. There are many Emoji that can only be understood in a Japanese context. If you are interested in learning about Japanese culture, this is a great place to start. I have a whole post below which goes into all the different Japanese specific Emoji.

Resources

Categories

Related Articles

絵文字 – The Japanese Meaning Behind Your Emoji’s Facial Expressions

Japanese Emoji (絵文字)👺 – The Hidden Culture in your Keyboard

ブイズ – All Eevee Evo or Eeveelutions in Japanese